Life-Path Alternative Character Generation for BRP (Basic Roleplaying)

By Nick Middleton

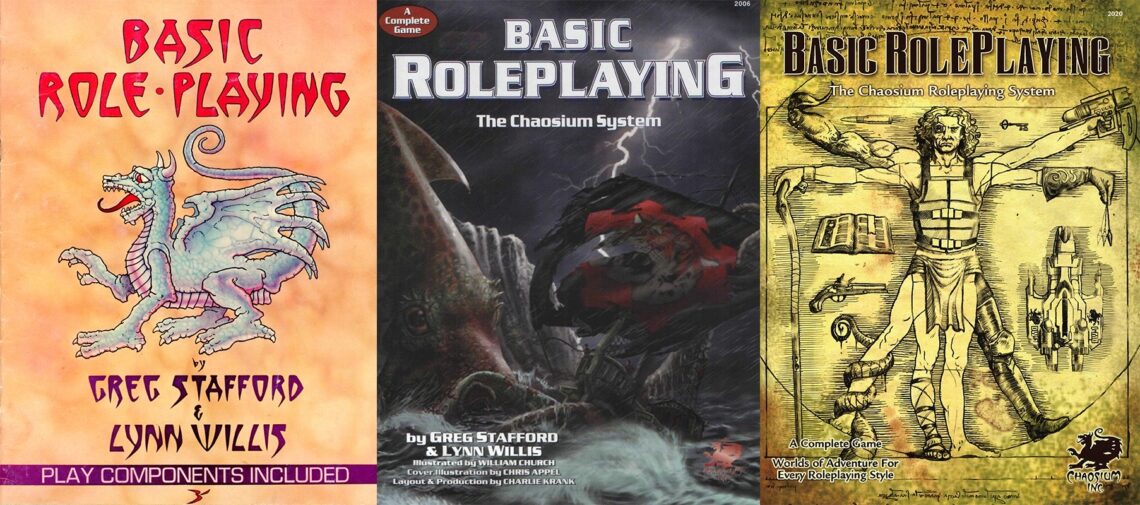

As an alternative to the simple skill point totals a player receives to divide amongst the skills of their characters chosen profession, I’ve developed this simple “life-path”system. My aim was to create a system that remained numerically compatible with the core BRP book, but introduced some of the flexibility of previous incarnations of BRP (such as the BRP monographs). Note that this system is not compatible with the use of the optional EDUcation statistic, nor the use of EDU for professional skill points.

Where possible I’ve used the same terms as in the core BRP book (albeit I only have an “Advanced Readers Copy” aka BRP Zero). (Now printed as the Big Golden Book) The system should cope with characters intended for any of the four “levels” of campaign: normal, heroic, epic or superhuman. Whilst this system makes calculations based on the character’s specific age, GM’s and players shouldn’t feel dictated to by this. In general, a group of characters created for a game should be equally important to the unfolding story created by playing the game, so everyone gets to feel fully involved in the game. One common way of ensuring this is to ensure that all player characters are at the same power level, and thus in normal BRP players will have the same skill points to assign for each character. With this life path system however, skill points are a direct function of the characters age and if a player chooses to have a character of significantly different age to the other player characters this may cause a problem. In the end it is up to the GM and players to decide whether they want to use this system.

A character’s life prior to entering play is divided in to two or three broad categories: Childhood, Development and, optionally, Maturity. The player receives some skill points from each category to spend on appropriate professional skills, and also devises (with the GM’s assistance and agreement) details related to their background appropriate to that phase of the characters life. This process substitutes for the professional skill point allocation in step 7 of character generation in the BRP core rule book (see page 22-23). Personal skill point allocation and all other steps of character generation occur as outlined (although, as noted earlier, this system doesn’t work with the optional Education statistic) in the core rule book.

In general, characters who possess Powers should have the normal number of starting powers as appropriate to the campaign level. GM’s might want to consider reducing the number of starting powers for characters that are starting play significantly younger than the BRP default of 18, especially for powers such as Magic and Sorcery that involve a degree of learning and arcane knowledge. In contrast Mutations and Psychic Powers might only begin manifesting at puberty, but once beyond that point a character could reasonably have all their initial powers. Super Powers are, predictably, harder to generalise about – but since a Character’s POW is unaffected by ageing, and Super Heroes is the role playing genre most likely to suffer from significant imbalance between character power levels, it’s probably best to build characters starting powers as per the rule book and then think about how to weave them in to the character history this system develops.

Players also choose one or more Significant Element for their characters for each period: an important piece of their background, related to that phase of their life somehow.

Starting Age

Standard BRP starting age is 17+1d6 years. Previous BRP game have used a wider spread of 15+2d6. GM’s should consider carefully whether they want a wide spread of actual ages or not, and whether they (or their players) will be bothered by a wide spread of character capability. As ever, you can consider the random spread as a range within which you can choose a specific value, rather than rolling the dice. The number of skill points assigned per year in this system are calculated to produce approximately the same amount of total skill points as a character would receive in the core BRP rules.

Childhood

This phase of a character’s life typically represents the years from their birth up to the age of about ten years. It is the period in which the character is categorically considered a minor and their well being is (or ought to be…) the responsibility of others. They may be in some form of formal education in the later part of this period, and certainly much of this period will (consciously or otherwise) have been spent learning about the world in which the character lives and the roles that various people the character comes in to contact with undertake.

The character gets 150 skill points to spend in skills from a profession they agree with the GM – this could represent their formal education in this period; exposure to a parent, relative or guardian’s profession; or the characters own precocious exploration of skills that interest them or help them survive. The player should be guided by the setting and the power level the GM has set – most eight year olds won’t be international assassins, but could well innocently learn to manipulate word wheels and decode messages using books whilst chatting with ”Uncle Yossil”, thus acquiring the basis of a skill in Science(Cryptography).

The GM should also be prepared to be flexible – if a player has a strong idea of what they want to end up playing then it is not unreasonable to allow a player to select a profession despite the fact that it seems unlikely that the character would have been exposed to at such a young age: the GM should use this as an opportunity to challenge the player to expand the characters background to explain how exposure to these diverse skills occurred.

Once skill points have been assigned, the player should pick at least one significant element (see below). GM’s may permit them to pick more, but even in a superhuman level campaign GM’s should be wary of packing too much in to a characters early life. As a rough guide, I would expect one significant element from Childhood for normal and heroic level campaigns, two for epic and three or possibly four for superhuman level campaigns.

Development

This period covers the characters development from a child to an adult, and in most settings will cover some portion of the years between eleven and twenty five years (splitting the difference between current BRP and “monograph” BRP’s maximum starting ages of 23 and 27 respectively). Again, depending on setting, this may involve a period of formal education (school and college, an apprenticeship) or actual work in a profession. For some of the period, in some settings, the character would likely still be classified as a minor and thus legally or socially the responsibility of someone else. In most settings this period is also one of transition – by the end of it in pretty much any setting the character is likely to be formally recognised as an adult and to be treated by their society as entirely responsible for their own actions; in many settings this transition will occur quite early in this period.

The player should break down the years in this period and assign them to Professions (from the list of those appropriate to the setting) agreed with the GM in blocks of at least 1 year. It is entirely conceivable that the character will only have one or two blocks – a character growing up on the streets of The Island City might have their Childhood and four years of Development in Thief, and the remaining years of Development (five years) in Sailor, having been forced to flee the city because of their previous exploits. GM’s should encourage players to “build up” the character they want to enter play by assigning blocks of years to appropriate professions and at the same time get the player to consider what the character was doing to acquire those skills: what does “fours years from 11 to 15 as a thief” mean they were living through? As ever, flexibility is the watch word here: whilst the GM and player must be respectful of the continuity of the chosen setting and style / level of the campaign, unusual choices should be seen as opportunities to develop interesting background rather than choices to be avoided or prohibited by the GM. Having said that of course the GM is the final arbiter and should be wary of permitting excessively baroque and exotic backgrounds.

| Campaign Level | Skill Points / Year |

| normal | 7 |

| heroic | 12 |

| epic | 17 |

| superhuman | 22 |

Characters gets a certain number of skill points (dependent on campaign level) per year in a block to be distributed in the professions skills. So four years in a profession in a normal campaign will give 28 skill points to divide between the professions listed skills, where as the same period in an epic campaign will provide 68 skill points to be distributed between the skills.

For each block of years during the Development period the player should create with the GM’s assistance and approval another significant element. As before, GM’s may permit the player more than one significant element per block, but again it is probably best not to over pack the character’s background with these things: the focus of the game is the character’s present, and that shouldn’t be overshadowed by all the details the player has invented (and might struggle to remember) for their past.

Maturity

Some character concepts only work if the character is substantial older than the relatively youthful twenty five years old. The grizzled war veteran, the retired police detective, the colonist seeking a new life: these are character concepts that only make sense with ages of thirty, forty or more. Subject to the ageing rules and GM permission, a character may choose to have a character significantly older than twenty five. They assign the years beyond twenty five in five year blocks to professions chosen as before and skill points are assigned against those professions as before, as follows:

| Campaign Level | Skill Points / 5 Years over 25 |

| normal | 5 |

| heroic | 10 |

| epic | 15 |

| superhuman | 20 |

So a 33 year old character would get 20 extra skill points in a superhuman level game (one full five year block), and a 50 year old character in a normal level game would get 25 extra skill points (five full five year blocks). As before, for each block of years, the player should develop a significant element of background detail with the GM’s assistance and agreement.

Significant Elements

For the characters Childhood, and for each block of years in Development (and possibly Maturity) the player has been asked to devise at least one significant element – but what do we mean by that? The Player should pick or create a person, place, object of event that resonates for the character. They may have no clear idea when they choose it as to what the significance is, and it can evolve in play: or they can have a specific element of their background tied to it. Here are a few suggestions to spark your imagination.

a) A person whom the PC would remember, or whom would remember PC, many years later. Not a contact or associate – simply a memorable encounter for one party or the other, or both.

- A Local Craftsman (cobbler, blacksmith, carpenter, sign painter, radio repairman, car mechanic) the character knew / pestered / stole from / helped.

- A Local Artist (painter, sculptor, poet, storyteller, composer, writer, dramatist) knew, was a subject of, inspired, annoyed, was tutored by.

- A Local priest / spiritual figure the character befriended, spied on, tormented, was tutored by.

- An eccentric outside to the characters community the character watched, was frightened off, spied on, learnt from.

- A family friend the character visited often.

- A respected figure (war veteran, retired leader, renowned figure) the character met, spied on, delivered groceries to, befriended, argued with.

b) A place of significance to the PC – somewhere the PC visited or was forced to go or was prevented from reaching or upon which the PC left a lasting impression or which impressed itself on the PC’s memory.

- One of the character’s homes during this period of their life.

- A particular place the character went for recreational purposes (to play, think, be alone).

- A particular place the character visited (i.e. chose to go to): somewhere that shocked, frightened, inspired, horrified or enchanted them.

- A particular place the character was sent (i.e. had no choice but to go to): somewhere that shocked, frightened, inspired, horrified or enchanted them.

- A particular place the character wished to go to but never did.

- A particular place the character day dreamed about (possibly invented or fictional).

c) An object – a favoured toy or trinket lost; a gift from a relative, an object of desire obtained or lost – a physical object that (whether or not the character still owns or it is even still in existence) left a strong memory with the character.

- A toy (yo-yo, stuffed animal, carved figure, toy weapon, puzzle).

- A memento (jewellery, locket, cane, rare book) of a person now deceased (or believed deceased).

- A statue, painting, book, recording device, or instrument (technical or musical) retrieved from destruction.

- A thing in a shop window, catalogue, museum or public display the character desired but never obtained.

- An object (stone, shell fragment, carving) from an exotic location the character has been, or has wanted to go to.

- A tool or instrument essential to a current or former interest or hobby of the characters or of friend or relative (possibly deceased).

d) An Event: the PC caused, participated in or was witness to an event that left a lasting impression on them. Could be a decisive moment in recent history (the death of a president) or something parochial (the death of the old cobbler in the PC’s home village) – but it should be an event that resonates in the PC’s life.

- A natural disaster – drought, earthquake, flood, storm, volcanic eruption – the character witnessed, was caught up in, or affected the character indirectly.

- A man made disaster – industrial accident, act of terrorism, transport accident, warfare – the character witnessed, was caught up in, or affected the character indirectly.

- A major public figure who died, was disgraced, unexpectedly came back to public attention and whom the character despised, venerated, knew or had some connection to.

- A minor public figure (from the characters original home or current place of residence) who died, was disgraced, unexpectedly came back to public attention and whom the character despised, venerated, knew or had some connection to.

- Closure, opening or radical change of facilities or landmark close to characters current or original home (building of a new road or bridge, closure of a port)

- Trivial incident whilst travelling or socialising that the character has subsequently decided or discovered was more important than they realised at the time.

Significant elements are intended to flesh out the character’s background by getting the player to think about concrete things in the character’s life before the game begins, and to provide the GM with pointers for things or themes they can use to weave the characters in to the setting. Some might even suggest forward plot lines, but that isn’t the primary goal: there are specific rules in the Super Powers section of the BRP Powers chapter about designing plot triggering elements of a character’s background, this system is about background elements that provide colour and texture to the character.

In high action, pulp games where PC’s are absolutely centre stage as unambiguous heroes and viewpoint characters, GM’s should think in terms of making specific use of significant elements from character backgrounds when developing the game – the sergeant a PC hated during the war SHOULD turn out to be the villain (or the villain’s main henchman); the Mine of Kurado where the PC was stationed for four years SHOULD be where the Villains bomb is planted and so on.

In lower key games, where the PC’s are more inhabitants of the world, and the GM’s aim is more verisimilitude , the significant elements of background are more useful for texture and colour. The sergeant at the fort can be described as reminding the Character of the one they hated during the war, the characters time at the Kurado mine is something they have in common with the foreman of the archaeological dig the characters need to get access to.

The difference is between melodrama in the first instance and drama in the second: in the former, coincidence and synchronicity are the norm; in the later whilst the character’s past informs their present circumstances and actions to a degree, it does not do so to the point of incredulity or destroying player and GM suspension of disbelief.

In exceptional circumstances, players may let the GM choose the significant elements for their character, but the GM should exercise caution in such circumstances. Whilst a player choosing to play an amnesiac might seem like carte blanche for the GM to indulge themselves, some players can find it very hard to enjoy playing a character they don’t know and which can be under cut at any moment by GM revelations. In such circumstances the GM should get a good idea of the parameters of character the player is happy with.